Alla fine la molteplicità delle figure geometriche – associate alla disponibilità di materiali

a diversa costitutività, formato, trattamento superficiale, colore – si contenderanno la

scena del piano di calpestio, con un grado ricorrente di regolarità e ricorsività (impostato,

in genere, sui moduli quadrati o rettangolari) o con un più alto “tasso” di variabilità e di

narratività capace di far lievitare il mondo tendenzialmente “lineare”, “piatto”, “omogeneo”

delle redazioni pavimentali più convenzionali.

Benché il tema pavimentale – per la sua specifica natura – metta in campo “fisicamente”

solo due dimensioni (larghezza e lunghezza) impedendo che l’emergere di qualsiasi rilievo

possa manifestarsi non sarà, comunque, impossibile introdurre la terza dimensione, sia

pur solo illusionisticamente mediante il disegno geometrico e il contrasto cromatico

dei materiali impiegati; allora – sulla superficie ottica – apparirà un alto e un basso,

un sopra e un sotto.

Il progetto pavimentale usa figure di puro contorno che si ordinano, si ripetono, si

rincorrono, si ritmano, si tessono reciprocamente; accostamenti e intersezioni sul piano

che tentano di mettere in valore forme, dimensioni, matericità, colori nelle loro possibili

e molteplici relazioni. Il pavimento diventa sempre disegno, a volte “disegno di disegni”,

fusione di motivi geometrici; ma spesso anche palinsesto anti geometrico, inteso come

narrazione figurale di storie, di eventi, di simboli.

Attraverso i secoli architetti, costruttori, trattatisti hanno ideato, codificato, trasmesso

schemi di base (archetipici), tipologie ricorrenti, repertori consolidati; ma dal canone

e dalle soluzioni convenzionali è stato sempre possibile discostarsi, negandole, variandole,

innovandole: alla “nudità” si è contrapposta spesso la “decorazione”; all’omogeneità

materica la polimatericità; al rigore – e alla ripetizione di schemi geometrici semplici –

si è anteposta la variazione figurativa (spesso anche di natura virtuosistica); dal colore

singolo si è passato bicromismo, se non all’esuberanza del policromismo. Centrale

è, indubbiamente, il ruolo del colore nel progetto pavimentale. Possiamo riguardare

i colori come una “seconda natura” delle figure geometriche – definibili, solo

astrattamente dalle linee di puro contorno – posti a contendersi, sin dalle origini, la

caratterizzazione delle redazioni pavimentali. I colori fisicizzano – al pari, o forse più,

delle figure – ogni corpo, ogni superficie apparente, connotandone la presenza come

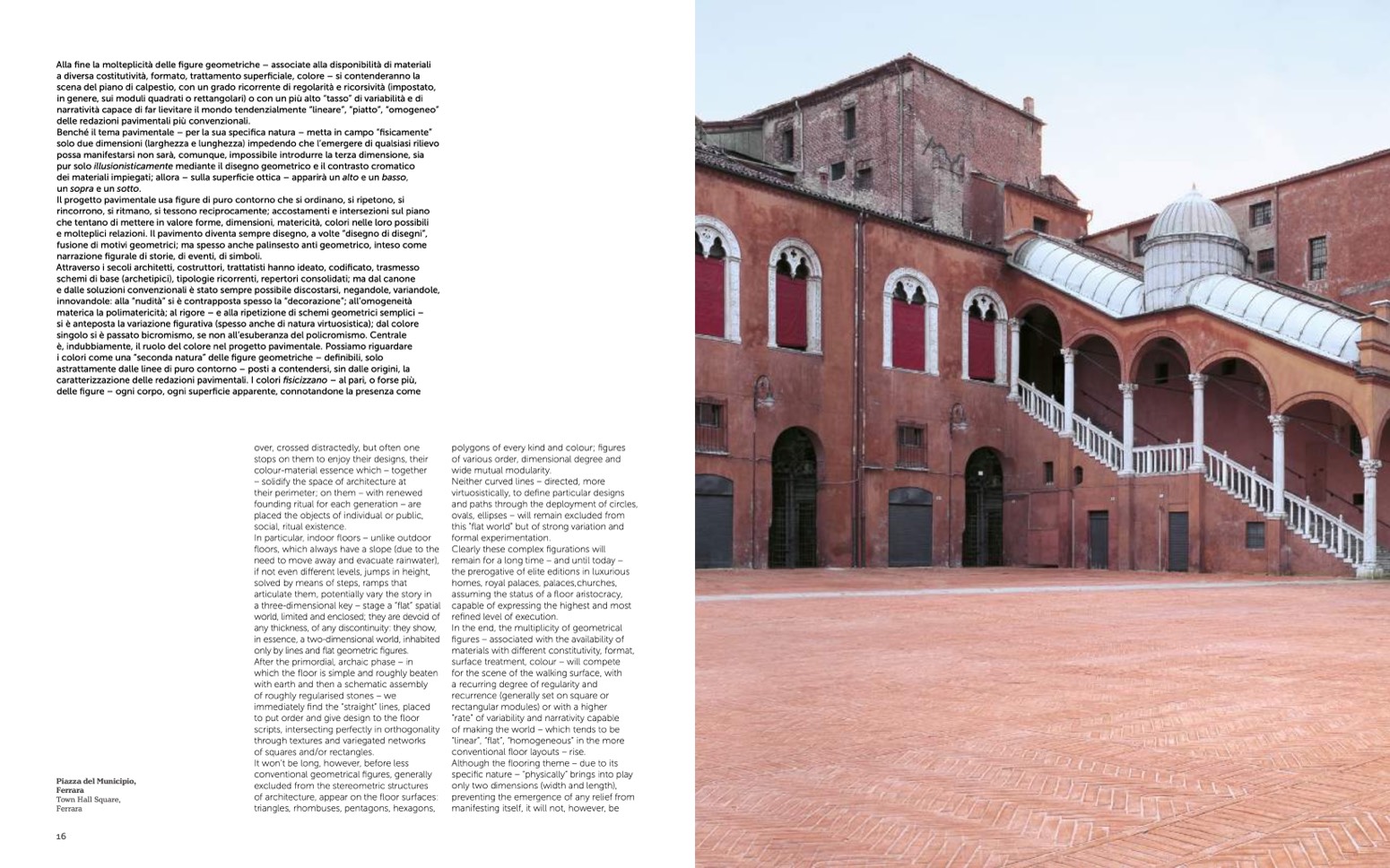

Piazza del Municipio,

Ferrara

Town Hall Square,

Ferrara

over, crossed distractedly, but often one

stops on them to enjoy their designs, their

colour-material essence which – together

– solidify the space of architecture at

their perimeter; on them – with renewed

founding ritual for each generation – are

placed the objects of individual or public,

social, ritual existence.

In particular, indoor floors – unlike outdoor

floors, which always have a slope (due to the

need to move away and evacuate rainwater),

if not even different levels, jumps in height,

solved by means of steps, ramps that

articulate them, potentially vary the story in

a three-dimensional key – stage a “flat” spatial

world, limited and enclosed; they are devoid of

any thickness, of any discontinuity: they show,

in essence, a two-dimensional world, inhabited

only by lines and flat geometric figures.

After the primordial, archaic phase – in

which the floor is simple and roughly beaten

with earth and then a schematic assembly

of roughly regularised stones – we

immediately find the “straight” lines, placed

to put order and give design to the floor

scripts, intersecting perfectly in orthogonality

through textures and variegated networks

of squares and/or rectangles.

It won’t be long, however, before less

conventional geometrical figures, generally

excluded from the stereometric structures

of architecture, appear on the floor surfaces:

triangles, rhombuses, pentagons, hexagons,

polygons of every kind and colour; figures

of various order, dimensional degree and

wide mutual modularity.

Neither curved lines – directed, more

virtuosistically, to define particular designs

and paths through the deployment of circles,

ovals, ellipses – will remain excluded from

this “flat world” but of strong variation and

formal experimentation.

Clearly these complex figurations will

remain for a long time – and until today –

the prerogative of elite editions in luxurious

homes, royal palaces, palaces,churches,

assuming the status of a floor aristocracy,

capable of expressing the highest and most

refined level of execution.

In the end, the multiplicity of geometrical

figures – associated with the availability of

materials with different constitutivity, format,

surface treatment, colour – will compete

for the scene of the walking surface, with

a recurring degree of regularity and

recurrence (generally set on square or

rectangular modules) or with a higher

“rate” of variability and narrativity capable

of making the world – which tends to be

“linear”, “flat”, “homogeneous” in the more

conventional floor layouts – rise.

Although the flooring theme – due to its

specific nature – “physically” brings into play

only two dimensions (width and length),

preventing the emergence of any relief from

manifesting itself, it will not, however, be

16

17