18

19

se, essi stessi, s’imponessero quale “finissima” e “impalpabile” entità; essenza ineffabile

della materia, ma anche dell’arte e di ogni artefatto umano investito da una fonte luminosa.

«Il colore – come ci indica Johann Wolfgang Goethe – occupa un posto assai elevato

nella serie delle manifestazioni naturali originarie, in quanto riempie di una molteplicità

ben definita il cerchio semplice che gli è assegnato. Non ci stupiremo quindi di

apprendere che esso esercita un’azione in particolare sul senso della vista, a cui esso

in maniera evidente appartiene e, per suo tramite sull’animo delle sue più generali

manifestazioni elementari senza riferimento alla costituzione o alla forma del materiale,

sulla cui superficie lo vediamo. Si tratta, diremo, di un’azione specifica quando il colore

sia preso nella sua singolarità, mentre, in combinazione con altri, si tratta di un’azione

in parte armonica, in parte caratteristica, spesso anche non armonica, sempre tuttavia

decisa e significativa che si riallaccia direttamente al momento morale. Questo è il motivo

per il quale il colore, considerato come un elemento dell’arte, può essere utilizzato come

un momento che coopera ai più elevati fini estetici».

1

Note

1

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, La teoria dei colori, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1999,

a cura di Renato Troncon, pp. 260, (ed. or Goethe Farbenlehre, 1810).

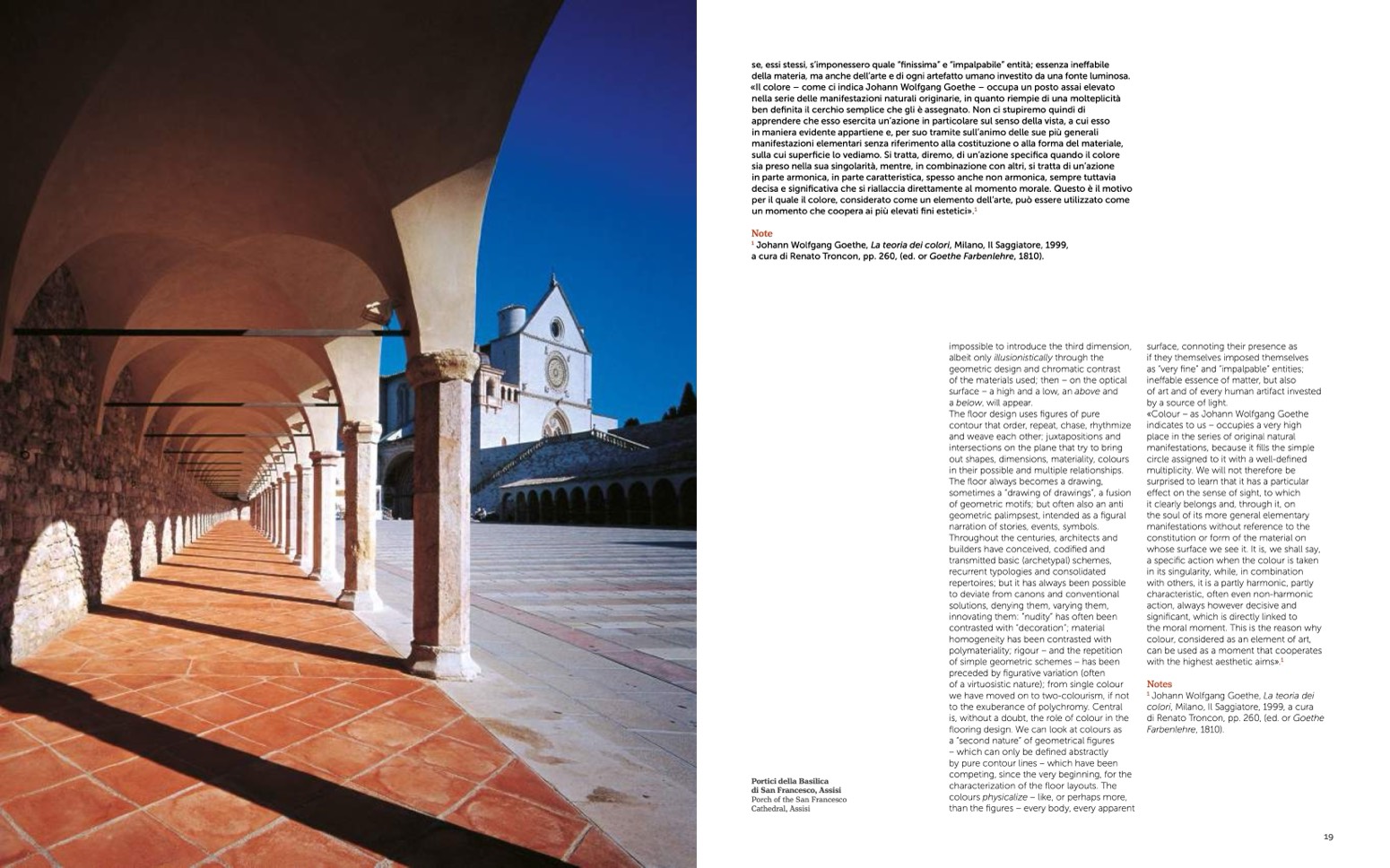

Portici della Basilica

di San Francesco, Assisi

Porch of the San Francesco

Cathedral, Assisi

impossible to introduce the third dimension,

albeit only illusionistically through the

geometric design and chromatic contrast

of the materials used; then – on the optical

surface – a high and a low, an above and

a below, will appear.

The floor design uses figures of pure

contour that order, repeat, chase, rhythmize

and weave each other; juxtapositions and

intersections on the plane that try to bring

out shapes, dimensions, materiality, colours

in their possible and multiple relationships.

The floor always becomes a drawing,

sometimes a “drawing of drawings”, a fusion

of geometric motifs; but often also an anti

geometric palimpsest, intended as a figural

narration of stories, events, symbols.

Throughout the centuries, architects and

builders have conceived, codified and

transmitted basic (archetypal) schemes,

recurrent typologies and consolidated

repertoires; but it has always been possible

to deviate from canons and conventional

solutions, denying them, varying them,

innovating them: ”nudity“ has often been

contrasted with “decoration”; material

homogeneity has been contrasted with

polymateriality; rigour – and the repetition

of simple geometric schemes – has been

preceded by figurative variation (often

of a virtuosistic nature); from single colour

we have moved on to two-colourism, if not

to the exuberance of polychromy. Central

is, without a doubt, the role of colour in the

flooring design. We can look at colours as

a “second nature” of geometrical figures

– which can only be defined abstractly

by pure contour lines – which have been

competing, since the very beginning, for the

characterization of the floor layouts. The

colours physicalize – like, or perhaps more,

than the figures – every body, every apparent

surface, connoting their presence as

if they themselves imposed themselves

as “very fine” and “impalpable” entities;

ineffable essence of matter, but also

of art and of every human artifact invested

by a source of light.

«Colour – as Johann Wolfgang Goethe

indicates to us – occupies a very high

place in the series of original natural

manifestations, because it fills the simple

circle assigned to it with a well-defined

multiplicity. We will not therefore be

surprised to learn that it has a particular

effect on the sense of sight, to which

it clearly belongs and, through it, on

the soul of its more general elementary

manifestations without reference to the

constitution or form of the material on

whose surface we see it. It is, we shall say,

a specific action when the colour is taken

in its singularity, while, in combination

with others, it is a partly harmonic, partly

characteristic, often even non-harmonic

action, always however decisive and

significant, which is directly linked to

the moral moment. This is the reason why

colour, considered as an element of art,

can be used as a moment that cooperates

with the highest aesthetic aims».

1

Notes

1

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, La teoria dei

colori, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1999, a cura

di Renato Troncon, pp. 260, (ed. or Goethe

Farbenlehre, 1810).