At the beginning of the Eighties, Paolo Portoghesi succeeded

in defining in a univocal manner the paradoxical and irritating

word that is postmodernism. Rather a redefinition than a new

label, his work was born from dissatisfaction with both previous

comparisons as with the jumble of heterogenous objects thrown

together under the modernist label. His new definition finally gave

us the possibility of putting together and contrasting different

elements. Postmodernism is seen as a break, refusal, negation

more than as the beginning of a new steering course. Very

many these days are no longer interested in ageing modernism

bequeathed to us by the Twenties’ movement with the precise

and rigid set of rules imbeded in a golden book that cannot be

disregarded. In that book were censured and treated as capital

sins all superfluous ornaments to everyday household goods, the

ornaments being themselves to blame.

The conviction that only what was useful could be pretty proved

to be one of the greatest and most dangerous utopias of the

rational age which started with a speech by Adolf Loos in which

he condemned all types of ornaments. Today, at last, ornaments

are back in favour, though not superflous decorations that weigh

down functional objects with useless decorations. The flavour of

the day is for an ornamentation that is both authentic and efficient

in rendering everyday objects more pleasing and converting

others: - as for example a table - into works of art without which

such objects would be but ordinary without life or fascination. And

mosaics carry out just that, helping save traditional ornamentation,

shuffling the cards to produce more than attractive results. The

rigid rules that constrained mosaic creation for so long have

finally fallen - mosaic has broken free from the its historical

obsession with the picturesque and architectural - it can now finally

put its essential qualities at the service of designers and creators.

Firstly a mosaic whatever the chosen design and in whatever way

on defines it is primarily a work of art for private as opposed to

public life. It belongs to that area of one’s private life best define

by the Anglosaxons as privacy with its sociological implications,

to one’s inner self: it is the center of a living space with a human

dimension full of objects for one’s own daily comfort. From its

inception, the mosaic is meant to become part of one’s family

life. The first known examples of floors, which date back to VIIIth

Century BC in Asia Minor, are multicolored mosaics which are of

the shape and design of carpets which are known to have been

weaved at the time. Compared to bare earth, mosaics had a

great advantage in that they could be swept or washed. One of

the words for mosaics in Greek says just that.

One of mosaics’ other qualities, present from the very conception

of the first mosaics and throughout its history is the easy

adaptation of fashionable materials to its realization. The oldest

mosaics of Asia Minor and Greece were made of small round

stone gathered in river beds, chosen for their color and variety,

a technic later on used by the Venezia artists, and known as the

“Venitian way”. Taking objects from their natural environment

and subverting their primary functions, the mosaic artist as well

as the designer invent new combinations and strive to create

decorations appropriate in a domestic context. In essence,

one can say that mosaic is the art of juxtaposition, and that in

juxtaposition it has found its true fulfilment. Of course, economic

conditions can change and the materials used can change from

the most precious to the most ordinary, but the arch principle of

“adaptation” remains the same.

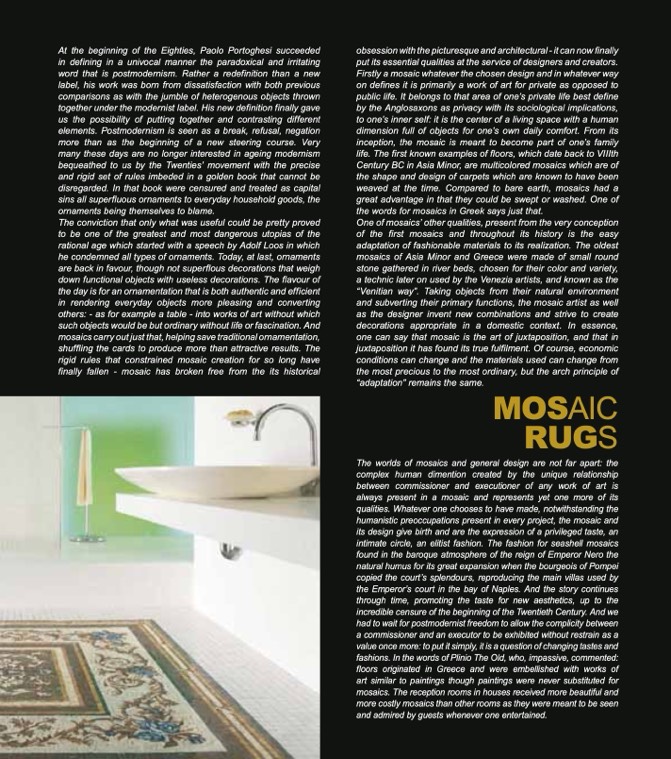

MOSAIC

RUGS

The worlds of mosaics and general design are not far apart: the

complex human dimention created by the unique relationship

between commissioner and executioner of any work of art is

always present in a mosaic and represents yet one more of its

qualities. Whatever one chooses to have made, notwithstanding the

humanistic preoccupations present in every project, the mosaic and

its design give birth and are the expression of a privileged taste, an

intimate circle, an elitist fashion. The fashion for seashell mosaics

found in the baroque atmosphere of the reign of Emperor Nero the

natural humus for its great expansion when the bourgeois of Pompei

copied the court’s splendours, reproducing the main villas used by

the Emperor’s court in the bay of Naples. And the story continues

through time, promoting the taste for new aesthetics, up to the

incredible censure of the beginning of the Twentieth Century. And we

had to wait for postmodernist freedom to allow the complicity between

a commissioner and an executor to be exhibited without restrain as a

value once more: to put it simply, it is a question of changing tastes and

fashions. In the words of Plinio The Old, who, impassive, commented:

floors originated in Greece and were embellished with works of

art similar to paintings though paintings were never substituted for

mosaics. The reception rooms in houses received more beautiful and

more costly mosaics than other rooms as they were meant to be seen

and admired by guests whenever one entertained.