EURIDICE

Euridice: note sulla collezione | Euridice: notes on the collection

The Euridice ceramics collection

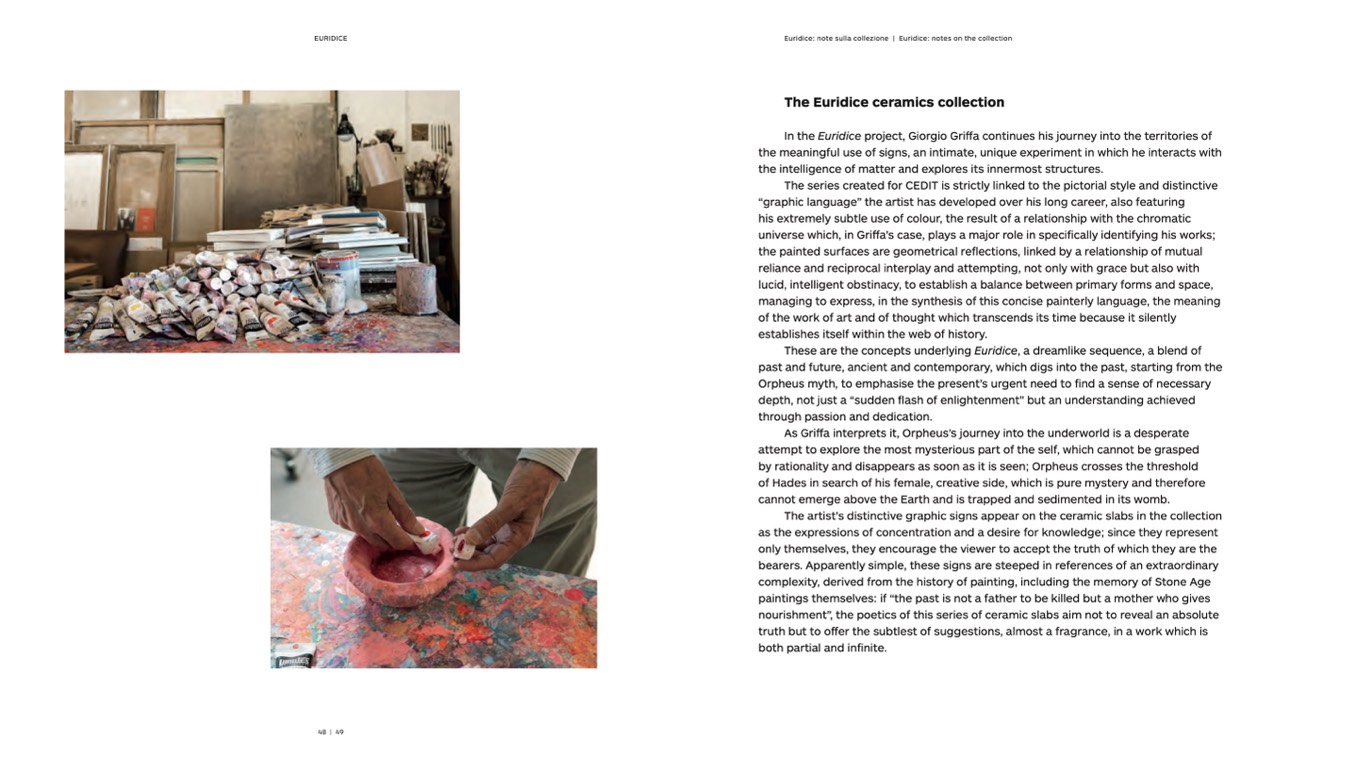

In the Euridice project, Giorgio Griffa continues his journey into the territories of

the meaningful use of signs, an intimate, unique experiment in which he interacts with

the intelligence of matter and explores its innermost structures.

The series created for CEDIT is strictly linked to the pictorial style and distinctive

“graphic language” the artist has developed over his long career, also featuring

his extremely subtle use of colour, the result of a relationship with the chromatic

universe which, in Griffa’s case, plays a major role in specifically identifying his works;

the painted surfaces are geometrical reflections, linked by a relationship of mutual

reliance and reciprocal interplay and attempting, not only with grace but also with

lucid, intelligent obstinacy, to establish a balance between primary forms and space,

managing to express, in the synthesis of this concise painterly language, the meaning

of the work of art and of thought which transcends its time because it silently

establishes itself within the web of history.

These are the concepts underlying Euridice, a dreamlike sequence, a blend of

past and future, ancient and contemporary, which digs into the past, starting from the

Orpheus myth, to emphasise the present’s urgent need to find a sense of necessary

depth, not just a “sudden flash of enlightenment” but an understanding achieved

through passion and dedication.

As Griffa interprets it, Orpheus’s journey into the underworld is a desperate

attempt to explore the most mysterious part of the self, which cannot be grasped

by rationality and disappears as soon as it is seen; Orpheus crosses the threshold

of Hades in search of his female, creative side, which is pure mystery and therefore

cannot emerge above the Earth and is trapped and sedimented in its womb.

The artist’s distinctive graphic signs appear on the ceramic slabs in the collection

as the expressions of concentration and a desire for knowledge; since they represent

only themselves, they encourage the viewer to accept the truth of which they are the

bearers. Apparently simple, these signs are steeped in references of an extraordinary

complexity, derived from the history of painting, including the memory of Stone Age

paintings themselves: if “the past is not a father to be killed but a mother who gives

nourishment”, the poetics of this series of ceramic slabs aim not to reveal an absolute

truth but to offer the subtlest of suggestions, almost a fragrance, in a work which is

both partial and infinite.

48 | 49